Lately, it seems that I’ve been spending far more time on creating blog entries (mostly on The Discerning Travelers) and trying to figure out Pinterest (in fairness, I’m once again teaching a course on Social Media to our graduate students this spring and need to keep up), than I have been doing real writing. I seem to have a notion that there is real writing and there is – other stuff. But what, precisely is real writing and why do I think it has to be my priority?

Lately, it seems that I’ve been spending far more time on creating blog entries (mostly on The Discerning Travelers) and trying to figure out Pinterest (in fairness, I’m once again teaching a course on Social Media to our graduate students this spring and need to keep up), than I have been doing real writing. I seem to have a notion that there is real writing and there is – other stuff. But what, precisely is real writing and why do I think it has to be my priority?

…just as I was considering this question, I opened up my email and found a message from one of my publishers. This is a publisher that I haven’t heard from in some two years – nope, not even a royalty statement – that is unless you count an email from someone in the office there suggesting that I pay them for the 100 books they sent to me that I did not order. When I told them that I would send them back to them when they sent me a royalty statement (because, as I mentioned casually to them, they were in breach of contract), I never heard from them again. Until today.

It seems that the company is being liquidated. Further, it seems that the authors were aware of this; the publisher herself is ill. Funny about that – I’m one of their authors and I didn’t know. So, what this means it that all rights to the book revert to me and I can do with it what I want. This raises a few important questions for an author.

First, I’m wondering what, if anything, I ought to do. I immediately sent them an email asking for a specific confirmation of the revision of all rights and for all of the electronic files related to the work. Which begs the second question…

What should I do with the files when I get them? What I am certainly not going to do is to buy their copies that are currently housed in a warehouse at the University of Toronto Press which distributes for them. I was never all that happy with the quality of the actual physical book in any case. So, if I do anything with it, I do it myself. Which leads to the next question…

Is the book still current enough for it to be made available on other terms? Since it is a memoir, it isn’t really out of date, and if a bit of effort were put into marketing (that was never done by the publisher in the first place – I did it all myself), it could re-emerge as both a physical book and as an e-book.

Is the book still current enough for it to be made available on other terms? Since it is a memoir, it isn’t really out of date, and if a bit of effort were put into marketing (that was never done by the publisher in the first place – I did it all myself), it could re-emerge as both a physical book and as an e-book.

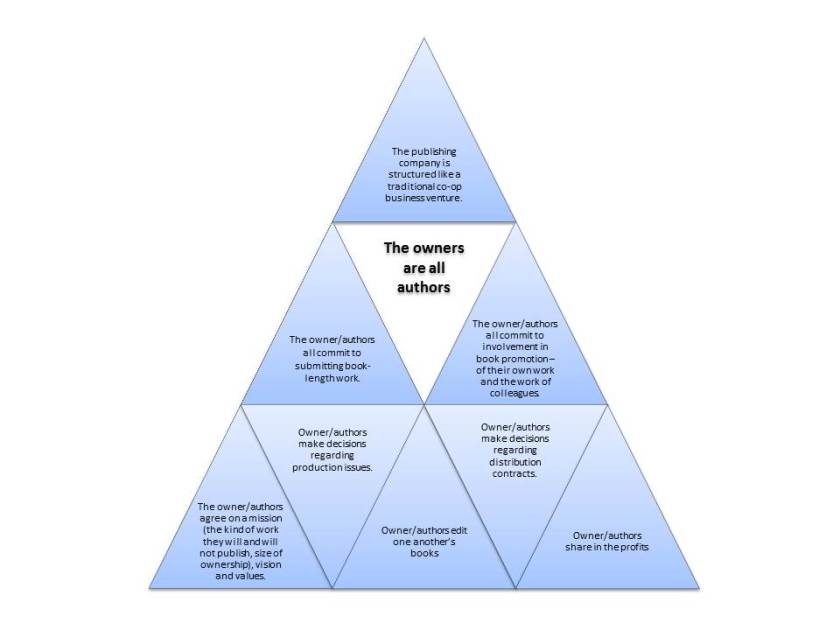

And all of this leads me to the final, and perhaps more philosophical question: Why did I even proceed with having it published by a traditional publisher in the first place? I could have done as good a job on my own, had as much reach on my own and kept control. This is a problem with many small publishing houses – they don’t have the resources needed to do a really professional job. I’ve reflected on the models of publishing before, and now I’m more convinced than ever that we do need to find a new model that captures the best of the traditional approach to publishing while at the same time manages to put the author front and center, rather than the publisher. The author needs to be in the driver’s seat in my view.

So, does all of this have any relevance to the question of real writing and the priority it need or need not have in a writer’s life? It does insofar as it takes me back to a piece of writing that, by all accounts, seems like real writing. And it gives me yet another reason to procrastinate from finishing the novel that languishes among the electronic files on my computer in a file titled…well, I’m not going to tell you yet.

Suddenly, my priority focus, for better or for worse, is on a book that I thought had been put to bed. Now I just have to decide if I should tuck it in and turn off the lights, or wake it up and have a party.